From Zero to Blinky in Ada

Recently, the Raspberry Pi Foundation launched their new RP2040 SoC on a $4 development board called Pico. As the foundation’s goal is primarily education, they’ve provided lots of high quality documentation, libraries, and examples for the new chip. Naturally, I’m going to ignore most of that and roll my own. Why? Because this is my idea of fun and I’m trapped inside during a pandemic.

If you’d like to build the examples and follow along, you’ll need GNAT Community 2020 ARM ELF installed in your PATH. I’ve only tested this on x86_64 Debian, if you’re on another platform I can’t help you. You’ll also want an SWD debugger that works with the RP2040. I use openocd on a Raspberry Pi, I hear Segger J-Link support is coming soon. Technically you could use elf2uf2 and load binaries over USB, but that’s gonna get tedious for any nontrivial debugging.

The RP2040 has no internal flash. The boot ROM loads 256 bytes of code from an external SPI flash and executes it. This “second stage bootloader” is expected to configure the XIP (eXecute In Place) peripheral with clock and timing details specific to the flash chip in use, then jump to the start of the user code in the memory mapped to the flash.

I tried to rewrite the boot2.S bootloader from pico-sdk in Ada, but I couldn’t get it to fit inside 256 bytes. It might be possible, but not today. I ran gcc’s preprocessor on boot2.S to generate a single assembly file I could link. I copied the linker script and crt0.S from pico-sdk too.

The zfp-cortex-m0p Ada runtime does most of the boilerplate Cortex-M0+ setup and implements Ada.Text_IO with semihosting over the debug interface, so I wrote a hello world and copypasta’d a GPR project file to build it.

with Ada.Text_IO; use Ada.Text_IO;

procedure Main is

begin

Put_Line ("Hello, RP2040!");

end Main;It took me a few hours to figure out the right incantation to get the linker to put the .boot2 section at the start of the flash chip along with crt0.S and the Ada runtime’s init code. The result is an ugly mess, which is why I’m omitting it here. If you want to see how to do things the quick and dirty way, my initial attempt is on github.

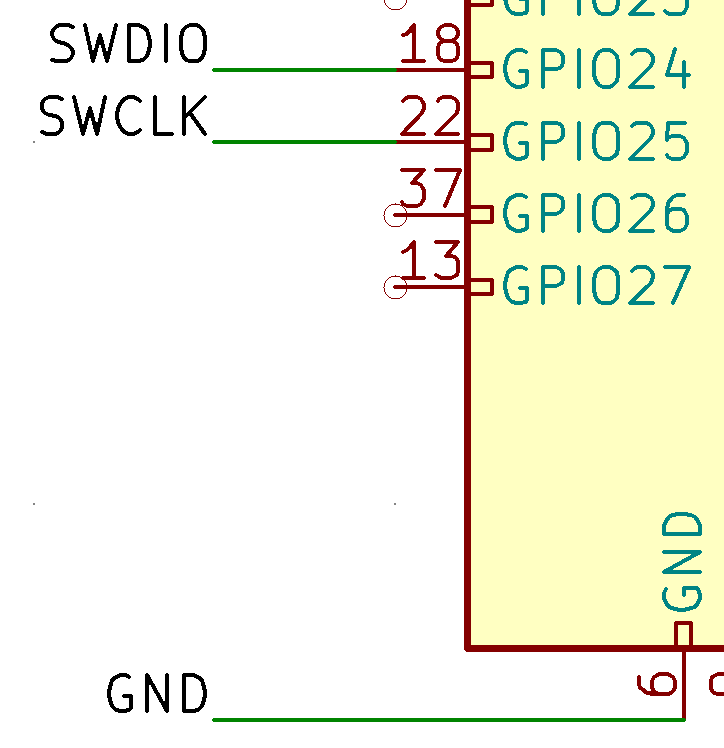

I soldered some headers for the Pico’s SWD port, wired it to a Raspberry Pi 4, and compiled the raspberrypi branch of openocd. As far as I can tell, nobody distributes a toolchain that can cross-compile Ada arm-eabi binaries on aarch64 and I don’t want to spend my time building binutils and gcc right now, so I setup an ssh tunnel from my x86_64 workstation to the Pi. I run arm-eabi-gdb locally and connect to openocd over the tunnel. Most of this will go in a .gdbinit script later.

ssh pi@192.168.1.202 -L3333:localhost:3333

openocd -f interface/raspberrypi-swd.cfg -f target/rp2040.cfg

arm-eabi-gdb obj/main

target extended-remote localhost:3333

monitor arm semihosting enable

load

run

Let’s write some code! For this example, I’m not going to do anything particularly complicated or idiomatic to Ada in order to keep things as simple as possible. This is going to be a very imperative program assigning values to registers and not much more.

ARM’s tooling for silicon vendors generates an SVD file, which is a pile of XML that lists all of the peripheral addresses and register offsets with vaguely human readable names. The svd2ada program translates this into Ada spec files with record types and representation clauses. Unfortunately, it crashed with the RP2040 SVD file. svd2ada expects a <size> to be specified on every register but the RP2040 SVD defines <size> at the peripheral level. The SVD format says this should then be inherited by the registers in the peripheral, but svd2ada doesn’t do that. I couldn’t figure out how to fix svd2ada so I wrote a quick Python script to modify the SVD file by copying the <size> field to every register within a peripheral. Now svd2ada works and generates a .ads file for each peripheral on the RP2040.

Normally the next step in bringing up a new chip would be to get all of the clocks configured, which is usually pretty boring code to write. At startup, the RP2040’s system clock runs from an internal ring oscillator with a not at all predictable or stable frequency between 1.8 and 12 MHz, which is good enough for some blinking. I skipped clock configuration and went straight for the GPIO.

There are four peripherals that need to be configured to toggle a pin: RESETS, PADS_BANK, IO_BANK, and SIO. RESETS, as you might expect, controls the reset state of the other peripherals. I pull the IO_BANK and PADS_BANK out of reset and wait for any initialization these peripherals might need to do in a busy loop.

RESETS_Periph.RESET.io_bank0 := False;

RESETS_Periph.RESET.pads_bank0 := False;

while not RESETS_Periph.RESET_DONE.io_bank0 or else not RESETS_Periph.RESET_DONE.pads_bank0 loop

null;

end loop;Next, PADS_BANK enables the output driver on GPIO25, which is connected to the LED on the Pico board.

-- output disable off

PADS_BANK0_Periph.GPIO25.OD := False;

-- input enable off

PADS_BANK0_Periph.GPIO25.IE := False;IO_BANK selects a peripheral to connect the pad to.

-- function select

IO_BANK0_Periph.GPIO25_CTRL.FUNCSEL := sio_25;The SIO (single-cycle IO) peripheral can toggle pins. I added a Pin_Mask constant in the declare block with bit 25 set. svd2ada generates nice subtype definitions for each register field so that I don’t need to know that GPIO_OUT is 30 bits wide. The immediate value here is just Shift_Left (1, 25), but using Shift_Left here would require some type conversion that I want to avoid in this example.

Pin_Mask : constant GPIO_OUT_GPIO_OUT_Field := 16#0200_0000#Enable the output in the SIO peripheral

-- output enable

SIO_Periph.GPIO_OE_SET.GPIO_OE_SET := Pin_Mask;Now we blink!

loop

SIO_Periph.GPIO_OUT_SET.GPIO_OUT_SET := Pin_Mask;

SIO_Periph.GPIO_OUT_CLR.GPIO_OUT_CLR := Pin_Mask;

end loop;Assuming those calls actually get compiled into single cycle writes, that’s gonna be blinking at half the system clock frequency, far faster than the human eye can see, but good enough for an oscilloscope. The SIO peripheral has an XOR register that allows us to make this code even shorter.

loop

SIO_Periph.GPIO_OUT_XOR.GPIO_OUT_XOR := Pin_Mask;

end loop;This is where the narrative diverges from reality. After I got to this point, I spent a few days refactoring the code into a package with well defined types and interfaces that conform to the Ada HAL package. For the sake of this example, I’m going to gloss over some of those organizational details and pretend things are still mostly happening in a single Main procedure.

Next I need a delay in that loop to blink at a rate that’s perceptible to humans. I could call a bunch of nop instructions and waste cycles, but that’s just silly. The RP2040 has a very nice 64-bit timer peripheral that I completely ignored because the chip also has the standard ARM SysTick peripheral that I’m already familiar with. Exported symbols need to be defined at the package level, so I’ve put this code into a SysTick package. I’ve only reproduced the implementation bits here, just know that this is happening in a new file.

-- Reload every 1ms

PPB_Periph.SYST_RVR.RELOAD := SYST_RVR_RELOAD_Field (12_000_000 / 1_000);

PPB_Periph.SYST_CSR :=

(CLKSOURCE => True, -- cpu clock

TICKINT => True,

ENABLE => True,

others => <>);I need an interrupt handler to increment a counter for every tick. crt0.S exports a weak isr_systick symbol that I can implement.

Ticks : Natural := 0;

procedure SysTick_Handler

with Export => True,

Convention => C,

External_Name => "isr_systick";

procedure SysTick_Handler is

begin

Ticks := Ticks + 1;

end SysTick_Handler;I’ll also add a wrapper around the wfi (wait for interrupt) assembly instruction in the same package

procedure Wait is

begin

System.Machine_Code.Asm ("wfi", Volatile => True);

end Wait;Back in the blink loop, I call the wait for interrupt instruction and check the value of Ticks.

loop

if SysTick.Ticks >= Next_Blink then

SIO_Periph.GPIO_OUT_XOR.GPIO_OUT_XOR := Pin_Mask;

Next_Blink := Next_Blink + 1_000;

end if;

SysTick.Wait;

end loop;IT BLINKS! Not precisely at 1 Hz, as the ring oscillator isn’t accurate, but close enough for this demo.